Jan Jedlička

Scroll, please

Jan Jedlička has been the subject of this portal for seven years. His pigments, photographic cycles or specially developed heliogravures are remarkable for their unabashed beauty, capturing the vanishing harmony of man and nature along with a perfection of execution. There is a humility of perspective, a respect for creation and the tradition of the old masters. Jan Jedlička does not transform or colour reality. He collects and grinds stones, and from this dust he produces pigments. As a precious relic, he then applies them to japanese handmade paper and exhibits them to compel us to remember how precious our country and culture are. He records what is disappearing, what has been and is now a mere imprint, preserving the ethos of our time. Hence his sceptical, yet lively and inquisitive view of a changing world.

Jan Jedlička is a profound observer who bears witness in a completely new way to a specific landscape, to the people and the peculiarities of the local culture. For 40 years he returned to the Tuscan Maremma, located near the city of Grosseto on the Tyrrhenian coast of the Mediterranean Sea. He came to know those places where marshes alternated with furrows of farmland and water channels and farmhouses. He captured the face, the soul and the breath of a landscape that man has struggled to transform over the centuries, whereas it keeps returning to its original form.

Jan Jedlička captures the world's remarkable visual and emotional qualities. In doing so, he employs an unusually large number of techniques - drawing, painting, graphics, photography and film, yet one perception does not overwhelm the other, but rather deepens it. He creates with more depth of feeling and reason, with aesthetic refinement, in technical perfection and purity. He worked as Chief Curator of the Museum in Winterthur, Switzerland, where he looked after the collection of modern and contemporary art. He restored works by Paul Klee, Giorgio Morandi, Pablo Picasso and Henry Matisse. The diligence, quality of workmanship and humility before the artwork that his profession demanded, he applies in his own independent work.

When he emigrated from Prague to Switzerland and Italy in 1969, he felt, in his own words, "like an earthworm that must grow back after an amputation". The new surroundings were so profound and different that he began to search for his artistic language anew. By that time he had graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague and was already expressing himself in his own way. The art historian Vojtěch Lahoda[1] called what Jan Jedlička painted in totalitarian Czechoslovakia "Prague Fantastic Realism". In exile, he seemed to have begun to limit the breadth of visual information and to intensify the impulses for our imagination. He was inspired by conceptual art (land-art) and Spurensicherung (forensics), but unlike his Western peers, he did not arrange the landscape or play at being a scientist collecting what he calls "pseudo-scientific data". He remained faithful to proven techniques.

Jan Jedlička drew the pigments for his paintings from his surroundings; he spent long hours dissolving the grain of large copper plates, which only prepared them for the actual creation and printing of the mezzotint. In the Hills and Trees series he again painted mirror images with acid on four different plates. The resulting juxtaposition required extraordinary concentration and imagination, although the fact that this is a printmaking technique, not watercolour, is known to few. Similarly, it is only after close examination that it becomes apparent that he captured the freshwater wetlands of Padua on old paper (from Renaissance Florence). He used a special camera to take the photographs, placing the horizon at the centre. NASA uses the same camera on space expeditions. The selected photographs are then printed by Kurt Zein in Vienna using a special graphic light-printing technique, because no one else can do it. The books of his photographic series are published by Gerhard Steidl, a German printer, publisher and former court photographer of Joseph Beuys. The books published by Steidl, who has so far only handled correspondence on a typewriter, will find their way into galleries around the world on the coattails of his reputation. As with Jan Jedlička, however, this is not an old-fashioned pose out of a desire to distinguish himself at any cost. They both honour what our ancestors invented and what has worked. They defy the dictates of the times, the fact that new necessarily means better. But they develop the new and the better, or come up with it themselves.

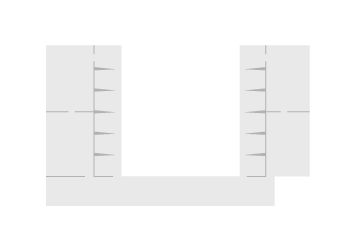

The Prague exhibition of Jan Jedlička, which was organised in summer 2021 by the Prague City Gallery and which we also gave "new life" to on the web, consists exclusively of works created after emigration. The exhibition was initiated and conceived by Vojtěch Lahoda, who unfortunately did not live to see it. It was prepared by Jitka Hlaváčková. The exhibition is not designed based on motifs, but according to the place of creation in Italy (Maremma and Grosseto), Switzerland (Rueschlikon), Great Britain (England, Ireland, Wales), on the way from Basel to The Hague and in Prague. The floor plan of the exhibition space is symmetrically divided into two parts - one where the works are in colour and one in black and white. You can choose where to start your tour, or you can walk through the exhibition with art historian Maria Rakušanová through an audio recording in each of the rooms.

The tour begins with colourful images called pigments. In the early 1990s, Jan Jedlička applied pigments to japanning stretched on canvas and placed them in grids. The colour here, as he says, "emerges through its vicinity". At other times the paintings are monochrome and the colour changes according to the reflection of the light during the day. Jan Jedlička applied up to six layers of pigment to the painting Terra rossa. He began with the lightest one so that it would shine through the successively darker layers. The old masters followed a similar process. They achieved a faithful skin tone (incarnate) with several layers of colour. The first base contained a pigment called Bohemian green earth, which was once very rare. You will see it in the second room in the portrait of the city of Great Green Prague. Here Jedlička no longer works with grids, because he says that a constructive system does not go with Bohemia.

For decades, in all seasons, Jan Jedlička observed the changing formations of the landscape with the water channels of the Tuscan Maremma. He observed the (dis)play of the elements and the permeability of the visible world.[2] He walked along an imaginary line (marked in pencil on the drawings), stopped after 20-30 steps and used the pigment of the earth's colour to capture what he saw. Cartographic drawings were created with the horizon at infinity. The red spots are water channels, the rest is unidentified space. The earth's bloodstream fades and regains strength with the change of the season. The flow of things in time and space is captured here. These are not exact records, however, but a completely new way of looking at a place, a completely different way than the rest of us are capable of.

Jan Jedlička's work in the period after his emigration was described by the Italian art critic Bruno Corá, who curated exhibitions of avant-garde artists such as the master of blue Yves Klein, the painter of space cutting through canvases Lucio Fontana, or Alberto Burri, a doctor who only began painting in prison as a prisoner of war. You can listen to the imposing Corá on a video recording during the tour. Corá came to Prague to see Jan Jedlička's exhibition. In art, the eye needs to physically appraise what it sees in reality. According to Bruno Corá, the colours used by Jan Jedlička have their "specific dustiness, dullness, they are tactile for the eyes, they can almost be touched with the eyes". We can see Jan Jedlička's works in person again in winter until 16 April 2023 at the Kunsthaus Zug in Switzerland: Kunsthaus Zug.

However, you can see high-quality reproductions of his works (from before and after his emigration), his films, his audio commentaries, curators' comments and their expert texts, etc. on this portal now, without travelling, in peace and as often as you wish. You can already adjust to Jedlička's meditative pace, feel the lightness, wit and at the same time the depth and seriousness of his message. In the film Air, which he made for the Swiss Centre for Global Dialogue and which you can also view here, the aerialist and environmentalist Bertrand Piccard speaks. According to him, we are not destroying our planet out of stupidity or selfishness, but because we do not realise the value of everything around us. Jan Jedlička sharpens our consciousness, reviving our sensitivity to nature and our respect for people who are in touch with their roots and searching for spiritual meaning. If we awaken this sensitivity in ourselves, perhaps we can survive with dignity. We have just learned that there are already over eight billion of us. But for the most part we are driven by senseless greed and continue to enjoy ourselves over the abyss to the point of stupidity. Even more urgently than at the time, Jesus' words from the Mount of Olives to the apostles come back to us, "Why are you sleeping? Get a grip on yourselves lest you enter into doom.” (Lk 22, 46). It would be a great pity if the work of Jan Jedlička were to become a beautiful epitaph for the remains of our planet.

Pavlína Bartoňová, Dezember 2021

[1] Vojtěch Lahoda was a leading expert on the history of modernism and the avant-garde in the Czech lands. He collaborated and became friends with Jan Jedlička. Together with curators Jitka Hlaváčková and Maria Rakušanová, he prepared an exhibition for Jan Jedlička and his two former classmates from the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague in 2016, which can be seen here. Vojtěch Lahoda and Jan Jedlička were instrumental in the publication of a monograph on the painter Jan Autenguber and the creation of a permanent exhibition of his works in his hometown of Pacov, more here.

[2] It is no coincidence that one of Jan Jedlička's works was chosen by the world-famous music label ECM for the cover of Jan Garbarek's album Visible World and for many other covers.

Prague City Gallery, Municipal Library

20. Mai 2021 - 5. September 2021

curator Jitka Hlaváčková

Jan Jedlička’s art is concerned with being in a landscape, observing and recording it in specific ways that differ from classic portrayals of landscapes in that they are not the outcome merely of viewing it, but of the artist’s entire sensory perception of landscape and how it changes in time and as he moves through it. The exhibition is structured to reflect how Jedlička proceeds through a landscape along the paths of his various creative strategies. It demonstrates how different techniques and media can be combined to create multi-layered images of places that are usually monitored over long periods of time. A photograph might be supplemented with a film, or printed as a photogravure or screen print, or transposed into a mezzotint or drawing, or a painting executed with Jedlička’s handmade pigments. Each work is always connected to a particular place and time, and for this reason the selection is arranged according to the three most significant geographical regions Jedlička has worked in: Italy, the British Isles and Bohemia.

In 1977 Jan Jedlička discovered the Maremma, a natural area in southern Tuscany across the sea from Elba. He found an old house near Grosseto, where for many years he would draw, paint, photograph and film. It was the Maremma that became key in Jedlička’s dialogue with landscape. To record its character he has developed a technique of painting with local pigments made from the minerals, clay, sand and dust he collects. He places these pigments next to one another on a canvas, or uses them to record elements of the landscape – mostly details of its irrigation canals, which create seemingly abstract motifs in his paintings. In drawings and print cycles he then records how time and motion change these elements’ appearance as he observes them. However, Jedlička’s main tools for working with time are photography, film and video. Films create a counterpoint to the technical precision of his photographs, approaching the same themes with an indistinct, abstract fluidity that reflects the principles at work in our perception of reality and time. His extensive photography series cover different times of day, different seasons, and changes in the weather and the water levels. This also brings into focus changes to the landscape caused by human intervention. The anthropological aspects of landscapes are an integral part of Jedlička’s mapping, and many of his films and photography cycles are partly or entirely concerned with documenting human activity.

This, Jan Jedlička’s first comprehensive exhibition, maps all the facets of his extensive oeuvre to show its structure in a complex yet coherent whole. His investigations of these landscapes and communities reveal him to be an artist, walker, explorer and observer with an extraordinarily open mind, someone who pays close attention to his surroundings.

Jitka Hlaváčková