Jan Křížek and the Paris Art Scene of the 1950s

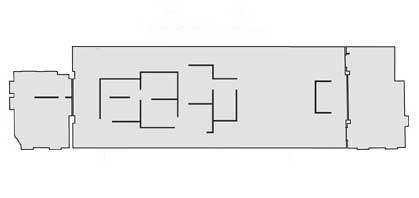

National Gallery in Prague, Wallenstein Riding Hall

31. May 2013 - 13. October 2013

Concept originator and curator, Anna Pravdová

The National Gallery in Prague presented a retrospective exhibition of Jan Křížek’s work at the Wallenstein Riding School. Of the many Czech artists who settled in France in the previous century, Jan Křížek (1919-1985) is one of the most original. From 1947 until his death, he lived in France, where he created a substantial part of his work. The impulses of Czech art were able to merge with contemporaneous currents in the postwar Parisian art scene and develop their own individual expression. Křížek was recognized by distinguished French theorists and artists, primarily Michel Tapié, Charles Estienne, André Breton, Jean Dubuffet, Pablo Picasso and René Duvillier. He presented his works in progressive Paris galleries and participated in several important collective exhibitions. In his work, we see how the results of his admiration for archaic and non-European art, early Romanesque stylization, Baroque expression and the work of Auguste Rodin combine in a unique way with a spontaneous, rapid gesture moving on the border of an automatic, intuitive and impulsive expression. In actuality, the process of his work was perfectly thought out, and he knew precisely where he was heading and what he was pursuing. When he concluded that he had achieved his goals, he ceased work at the age of forty-four and moved from Paris to the French countryside.

Although he was first and foremost a sculptor, he left behind a rich collection of drawings and graphic work. At the beginning of the 1950s he worked for several years in a small servant’s quarters, where he lived with his wife. He met with no one. He drew, made small statuettes of wood and clay. He wanted to prepare himself properly before presenting his works to the public once again. Since he did not have the money to buy raw materials, he would often recycle material. He would break up and crush his statuettes, soak the clay and begin modeling again. First he would draw on the paper then dip it in water or ink, and finally he would carve figures into it. He worked with various scraps, envelopes, or paper tablecloths, which his wife Jiřina brought home from work. This resulted in colorful engraved drawings, the technology of which was influenced by the artist’s material deficiency, yet which corresponded to contemporary artistic techniques of the time. In 1954, he created a cycle of black-and-white lithographs in the workshop of the Parisian lithographer and typographer Jean Ponse, through whose studio passed a number of prominent artists. In order not to bind himself to someone else’s workshop, Křížek then went from lithography to linocuts, which he worked on in his miniature Parisian dwelling. In 1956 he created a set of black-and-white linocuts, and between 1958 and 1961 colored linocuts. Here he once again explores the possibilities of an “authentic” display of the human figure.

The peak of Křížek’s work is stone and wooden statues, which he created from 1947 to 1948 in the Parisian atelier of the Spanish sculptor Honoria Condoye, in 1948 at a farm in central France near Marie and Oldřich Dubinová, and during a summer stay in Gordes and Brittany in 1955 and 1956.

The turn of the 1950s and 1960s was a hectic creative period for Křížek, when he launched a series of new experiments. He created several drawings with pastel on newsprint and also set to work on collages. It is a specific chapter of Křížek’s work, deviating from his previous spontaneous and “raw” approaches, even though he was once again composing pictures of a human, or a group of human, figures from scraps of paper, sometimes combined with drawing.

At the beginning of the 1960s, he created a series of paintings and a number of sketches with watercolor or gouache, in which he recapitulated the main problems he was dealing with in his work—that is, the many ways of depicting the human figure. In 1962, he ceased creating, convinced that he had solved his problem. Characteristically he did not provide any of his works with names; for him what was important was his own process of searching, continuity and development: drawings and statues were “mere” stages on the way to cognition.

The exhibition follows the artist’s fortunes and the development of his work. It presents twenty years of Křížek’s vigorous creative activity and presents many of his previously unknown works, which have been borrowed from both public and private collections in the Czech Republic, as well as from important museums and collections in France (Fonds régional d'art contemporain Limousin, Fonds régional d'art contemporain Bretagne, Musée de la Cohue, Vannes, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Brest, and the collection abcd.). Křízek’s work is complemented by the works of his friends and peers, whom he personally knew and who were artistically close to him. His work, through hints and suggestions, are embedded within the international context of post-war art: it demonstrates a close creative affinity with the work of Václav Boštík, with whom during World War II Křížek examined in a number of drawings the interrelationships of colors and lines, questions of the articulation of planes and space and their rhythmic division.

Shortly after Křížek arrived, his work was represented at the first exhibition of a new exhibition space, Jean Dubuffet’s Foyer de l’art brut, devoted to the exhibition of works which went beyond the usual canons of artistic production, and for which Dubuffet introduced the designation art brut. We partially reconstruct this introductory presentation from the autumn of 1947 as part of Křížek’s retrospective. Between 1948 and 1949, Křížek spent several months in a region of France that had a hundred-year pottery tradition. He created a large set of kitchen utensils and free works, all in his own primitivizing style. He was allowed to work there at the intercession of Pablo Picasso, who was also making ceramics there at the same time. Picasso's ceramic art will be represented at the exhibition thanks to a loan from the Picasso Museum in Barcelona.

In the fifties Křížek's work was supported and exhibited by the main theorist of lyric abstraction and Tachisme, Charles Estienne. The circle of artists gathered around Estienne, to which Křížek belonged at that time, are represented here by the drawings of René Duvillier.

The distinctive primitivizing style of the representation of female figures on Křížek’s canvases and drawings resonates with the contemporaneous work of Jean Dubuffet, especially his Corpes des Dames series, two drawings of which will also be on display. In the second half of the 1950s, Jan Křížek attended meetings of the surrealist group and carried on an interesting correspondence with André Breton. Breton also exhibited his work in his own gallery in Paris.

An extensive monograph by Anna Pravdová has been published for the exhibition, “Man Must Always Be Inherent in My Work” Jan Křížek (1919-1985), A documentary film by Martin Řezníček Jan Křížek, statues and bees (2008) can also be seen at the exhibit.

Anna Pravdová

ANNA PRAVDOVÁ (born 1973). She studied French and art history at Charles University in Prague and art history at the Sorbonne in Paris. She focuses on the art of the twentieth century, primarily Czech-French relations in the arts and on the activities of Czech artists abroad. She is currently working as a curator in the National Gallery in Prague.